In a world increasingly conscious of cultural bias and historical distortion, the call to “decolonize” knowledge invites us to revisit the very foundations of how we learn. Traditional academic disciplines—from anthropology to literary studies—often center Western canons, sidelining or outright ignoring perspectives from the Global South and Indigenous communities. This imbalance perpetuates myths about intellectual hierarchies, feeding into broader social injustices. Yet, transformative thinkers across continents have long worked to expose these structural blind spots.

Below, you’ll find five pivotal texts that question Eurocentric frameworks. Each highlights alternative epistemologies, critiques colonial legacies in scholarship, and challenges us to rethink what it means to “know.”

Orientalism by Edward W. Said

A Groundbreaking Critique of Western Portrayals of the “East.”

First published in 1978, Orientalism dismantles how Western academics, artists, and politicians have created a distorted image of the Middle East and Asia. Edward Said argues that these stereotypes—often romanticized, infantilized, or exoticized—served to justify European and American imperial ambitions. By analyzing texts from literature and travelogues to political speeches, Said reveals how “knowledge” itself can become an apparatus of power.

Why It Matters: Said’s work remains foundational in understanding cultural representation and the political stakes of scholarship. His methodology set the stage for postcolonial studies, reminding us that how we depict others shapes both perceptions and policy.

Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples by Linda Tuhiwai Smith

Reclaiming Indigenous Epistemologies to Transform Research Practices

Linda Tuhiwai Smith, a Māori scholar, illuminates how colonial frameworks have dictated not just what we research about Indigenous peoples, but how we conduct that research. Drawing on her cultural and academic background, she demonstrates how Western methodologies can perpetuate colonization by dismissing Indigenous knowledge systems. The book offers strategies for reshaping research protocols and ethical guidelines so that Indigenous communities serve as agents, not objects, of scholarly inquiry.

Why It Matters: Smith’s work goes beyond critique; it offers a practical roadmap for ethical engagement and respectful collaboration. It challenges our assumptions about objectivity, expertise, and the ownership of knowledge.

Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

Language as Both a Battleground and a Vehicle for Liberation

In this seminal essay collection, Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o explains how English was imposed through colonial education systems, effectively marginalizing African languages and traditions. By exploring literature, theatre, and oral storytelling, Ngũgĩ reveals how language can be weaponized to suppress or harnessed to empower. His decision to write primarily in Gikuyu is both an act of defiance and a call for cultural self-determination.

Why It Matters: Ngũgĩ’s arguments resonate across all postcolonial contexts, where linguistic choices reflect broader battles for identity, dignity, and autonomy. In an era of global English dominance, he reminds us of the political dimensions of language and translation.

Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History by Michel-Rolph Trouillot

Uncovering How Histories Are Created, Erased, and Revised

Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot delves into how narratives become “official history” and whose voices get erased in the process. From the Haitian Revolution to the Alamo, Trouillot shows that historical accounts are shaped by power relations—sometimes subtly, sometimes overtly. His thesis is a meticulous exploration of how fragile the idea of “truth” can be.

Why It Matters: Trouillot’s analysis is essential for anyone questioning why certain stories make it into museums and textbooks while others fade into oblivion. His insights on power dynamics in historical production resonate with today’s debates over monuments, archives, and contested memory.

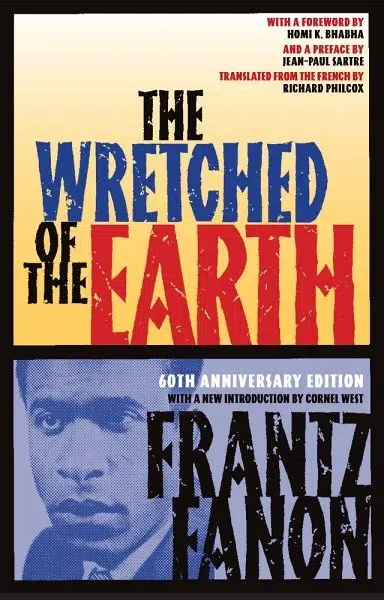

The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon

A Rallying Cry for Anti-Colonial Struggle and Psychological Liberation

Written during Algeria’s fight against French colonial rule, Fanon’s manifesto probes the psychological and cultural violence inflicted by colonization. He argues that the colonized must reclaim their sense of self through revolutionary action, both physical and intellectual. Despite its historical context, this explosive text remains a searing critique of oppression that resonates far beyond the mid-20th century.

Why It Matters: Fanon’s urgent call for dignity and self-actualization continues to speak to oppressed communities globally. His analysis reveals the deep scars colonialism leaves on both individual psyches and collective identities.

Conclusion

From Edward Said’s pioneering critique of cultural representation to Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s radical reframing of research ethics, these five texts illustrate that knowledge is never neutral—it reflects and reinforces the power structures that produce it. By exposing Eurocentric biases, each author challenges us to examine how we learn, whose histories we validate, and how our institutions continue (or resist) colonial legacies.

The pursuit of “decolonized” knowledge is an ongoing process of self-reflection and institutional transformation. It asks us to question habitual assumptions, uplift marginalized perspectives, and dismantle barriers to inclusion in scholarship and public discourse. As we explore these works, consider how their insights might reshape your own intellectual practice—be it rethinking research methods, advocating for Indigenous languages, or pushing for curriculum reforms. By doing so, we not only expand our understanding of the past but also affirm the diverse cultural tapestry that shapes our shared future.

Which text resonates most with you? Please share your thoughts in the comments.